_______________________

Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944)

![]()

Again today we take a look at the movie “The Longest Ride” which visits the Black Mountain College in North Carolina which existed from 1933 to 1957 and it birthed many of the top artists of the 20th Century. In this series we will be looking at the history of the College and the artists, poets and professors that taught there. This includes a distinguished list of individuals who visited the college and at times gave public lectures.

The Longest Ride Official Trailer #1 (2015) – Britt Robertson Movie HD

It has been my practice on this blog to cover some of the top artists of the past and today and that is why I am doing this current series on Black Mountain College (1933-1955). Here are some links to some to some of the past posts I have done on other artists: Marina Abramovic, Ida Applebroog, Matthew Barney, Aubrey Beardsley, Larry Bell, Wallace Berman, Peter Blake, Allora & Calzadilla, Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Heinz Edelmann, Olafur Eliasson, Tracey Emin, Jan Fabre, Makoto Fujimura, Hamish Fulton, Ellen Gallaugher, Ryan Gander, John Giorno, Rodney Graham, Cai Guo-Qiang, Jann Haworth, Arturo Herrera, Oliver Herring, David Hockney, David Hooker, Nancy Holt, Roni Horn, Peter Howson, Robert Indiana, Jasper Johns, Martin Karplus, Margaret Keane, Mike Kelley, Jeff Koons, Richard Linder, Sally Mann, Kerry James Marshall, Trey McCarley, Paul McCarthy, Josiah McElheny, Barry McGee, Richard Merkin, Yoko Ono, Tony Oursler, George Petty, William Pope L., Gerhard Richter, Anna Margaret Rose, James Rosenquist, Susan Rothenberg, Georges Rouault, Richard Serra, Shahzia Sikander, Raqub Shaw, Thomas Shutte, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Mika Tajima,Richard Tuttle, Luc Tuymans, Alberto Vargas, Banks Violett, H.C. Westermann, Fred Wilson, Krzysztof Wodiczko, Andrea Zittel,

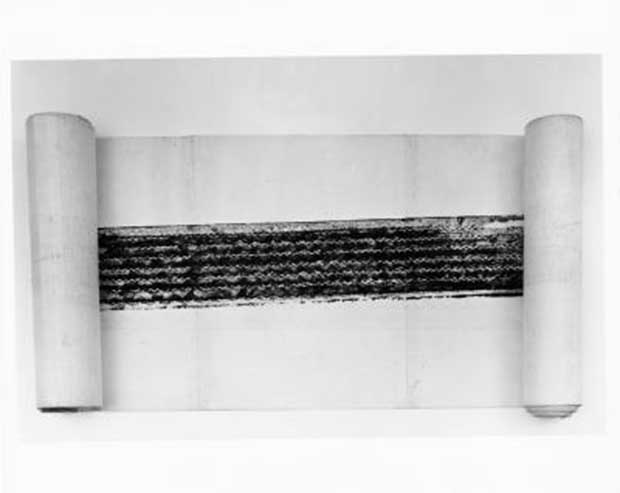

My first post in this series was on the composer John Cage and my second post was on Susan Weil and Robert Rauschenberg who were good friend of Cage. The third post in this series was on Jorge Fick. Earlier we noted that Fick was a student at Black Mountain College and an artist that lived in New York and he lent a suit to the famous poet Dylan Thomas and Thomas died in that suit.

The fourth post in this series is on the artist Xanti Schawinsky and he had a great influence on John Cage who later taught at Black Mountain College. Schawinsky taught at Black Mountain College from 1936-1938 and Cage right after World War II. In the fifth post I discuss David Weinrib and his wife Karen Karnes who were good friends with John Cage and they all lived in the same community. In the 6th post I focus on Vera B. William and she attended Black Mountain College where she met her first husband Paul and they later co-founded the Gate Hill Cooperative Community and Vera served as a teacher for the community from 1953-70. John Cage and several others from Black Mountain College also lived in the Community with them during the 1950’s. In the 7th post I look at the life and work of M.C.Richards who also was part of the Gate Hill Cooperative Community and Black Mountain College.

In the 8th post I look at book the life of Anni Albers who is perhaps the best known textile artist of the 20th century and at Paul Klee who was one of her teachers at Bauhaus. In the 9th post the experience of Bill Treichler in the years of 1947-1949 is examined at Black Mountain College. In 1988, Martha and Bill started The Crooked Lake Review, a local history journal and Bill passed away in 2008 at age 84.

In the 10th post I look at the art of Irwin Kremen who studied at Black Mountain College in 1946-47 and there Kremen spent his time focused on writing and the literature classes given by the poet M. C. Richards. In the 11th post I discuss the fact that Josef Albers led the procession of dozens of Bauhaus faculty and students to Black Mountain.

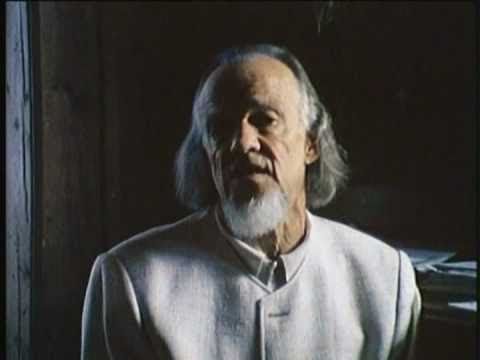

In the 12th post I feature Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) who was featured in the film THE LONGEST RIDE and the film showed Kandinsky teaching at BLACK MOUNTAIN COLLEGE which was not true according to my research. Evidently he was invited but he had to decline because of his busy schedule but many of his associates at BRAUHAUS did teach there.

![]()

Friends in Exile: A Decade of Correspondence, 1929–1940

- Edited and with an introduction by Jessica Boissel; Foreword by Nicholas Fox Weber

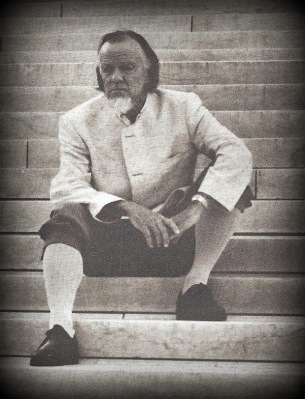

Josef Albers (1888–1976) and Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944), artists and teachers at the Bauhaus, were exiled from Germany when the school was forced to close in the early 1930s. The 46 letters in this volume document the intimate exchange between these two friends in a period when the world was coming apart. Despite the tumult, each wrote to the other of his continuous creative evolution, while also providing rich impressions of his new world. For Kandinsky, this was Paris where he navigated a new avant-garde scene. For Albers, it was the United States where he and his wife Anni began teaching at the recently founded Black Mountain College in North Carolina. Kandinsky’s and Albers’s correspondence reveals their warmth and humor, their strength in coping with unexpected circumstances, and above all their conviction in the resilience and power of art. Archival photographs, artwork, and ephemera accompany the collection, which brings together the artists’ full extant correspondence for the first time in English and German.

Jessica Boissel was collections curator at the Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. Nicholas Fox Weber is the executive director of the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation.

Bauhaus: Art as Life – Talk: An Insider’s Glimpse of Bauhaus Lfe

In the book “Albers and Moholy-Nagy: From the Bauhaus to the New World,” By Achim Borchardt-Hume, Tate Modern (Gallery) it is noted that J.A. Rice, head of BLACK MOUNTAIN COLLEGE, invited Wassily Kandinsky and his wife Nina to come to the college and he told them they could find more supporters in the USA and get more representation in NY Galleries and even possibly a show at the Museum of Modern Art in NY, but they said had to put off a trip. However, in the movie THE LONGEST RIDE, Kandinsky is seen lecturing at Black Mountain College which may have actually happened since many distinguished guests did visit the college and lecture to the local community in the process.

![Haus party … students at the Bauhaus in 1931. Photograph: Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau]()

Motif

![Bauhaus canteen,Bauhaus canteen, Dessau 1930 Museum of Contemporary Art Zagreb]()

Personally I had a pretty intimate experience with the term “Bauhaus”. I graduated from an old liberal art college in New York who followed a Bauhaus course arrangement in their undergraduate Art Department. I lived in a new Bauhaus style dorm in my first year there. I later studied post-war architecture history with an emphasis on Bauhaus.

I didn’t like it at the time. I did not take all the required classes in art department. I did not like the dorm’s height or contour that blocked my view when I was walking. I did not like the inner design of it that did not serve its purpose. I did not like the Bauhaus slides in my favorite architecture history class because they were impressively ugly.

To some extent, coming across this term in art history study aroused my memory at the east coast. Now given this chance, I seriously revisited this term and felt refreshed towards it.

Bauhaus Story

![Lucia Moholy Photograph by Michael von Graffenried 1987]()

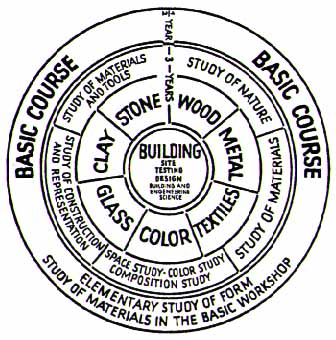

Bauhaus 1919-1933 – A Chronology

The Bauhaus occupies a place of its own in the history of 20th century culture, architecture, design, art and new media. One of the first schools of design, it brought together a number of the most outstanding contemporary architects and artists and was not only an innovative training centre but also a place of production and a focus of international debate. At a time when industrial society was in the grip of a crisis, the Bauhaus stood almost alone in asking how the modernization process could be mastered by means of design.

Founded in Weimar in 1919, the Bauhaus rallied masters and students who sought to reverse the split between art and production by returning to the crafts as the foundation of all artistic activity and developing exemplary designs for objects and spaces that were to form part of a more human future society. Following intense internal debate, in 1923 the Bauhaus turned its attention to industry under its founder and first director Walter Gropius (1883–1969). [16]

![Henry van de Velde’s building of 1904, housed The Bauhaus from 1919 to 1925.]()

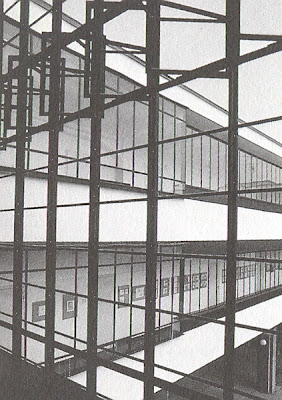

Dessau Period 1925-1932 – Prosperity of Bauhaus

The Dessau phase of the Bauhaus is characterized by the consolidation of its orientation towards the new unity of art and technology, which was initiated in Weimar in 1923. In Dessau, the Staatliches Bauhaus became the Hochschule für Gestaltung (school of design). In a departure from craftsmanship, there were now professors and students in place of masters, journeymen and apprentices. In the aspiring industrial city of Dessau, the Bauhaus found the ideal environment for the design of models for industrial mass production. [17]

Surprisingly, following the politically motivated closure of the Bauhaus in Weimar, the change of location to Dessau did not result in a crisis in the school. If anything, it fostered its consolidation on the path to the design of new industrial products for the masses.[17]

On Gropius’s recommendation, the director’s post was handed over to the Swiss architect and urbanist Hannes Meyer, previously the head of the architectural department established at the Bauhaus in 1927. Cost-cutting industrial mass production was to make products affordable for the masses. His rallying cry at the Bauhaus was, “The needs of the people instead of the need for luxury.”[17] Despite his successes, Hannes Meyer’s Marxist convictions became a problem for the city council amidst the political turbulence of Germany in 1929, and the following year he was removed from his post. [17]

With Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in 1930, the Bauhaus acquired its last and – in contrast to Gropius and Meyer – least politically minded director. The school’s orientation towards architecture grew under his direction; however, there was also an increasing lack of socio-political reference.[17] The students were most affected by the ban on any type of political activity and the discontinuation of production lines. Under Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, the Bauhaus developed from 1930 into a technical school of architecture with subsidiary art and workshop departments.[17] After the Nazis became the biggest party in Dessau at the elections, the Bauhaus was forced to move in September 1932. It moved to Berlin but only lasted for a short time longer. The Bauhaus dissolved itself under pressure from the Nazis in 1933. [17]

![Walter Gropius’ building for Dessau Bauhaus.]()

Recently I read The Bauhaus Ideal: Then and Now. In the book, William Smock presented a vivid overview of the Modernist design and its legacy. I got to know more about the famous Bauhaus dictums “form follows function”, “truth to materials” ,”less is more”.

The Bauhaus story first started out as a school of design. Walter Gropius was the first director of this modern art and design school called Bauhaus. It was an invented word: BAU = Building , HAUS = House. He wanted to unify arts, combining fine art and design. So people could see and use aesthetically pleasing, yet functional artworks/products. However, the Bauhaus school had to go through ups and downs. It had altogether three directors which represented three different periods. It was controlled by Nazis and forced to shut down for good during WWII. Later, it got rebuilt as “the Black Mountain College” in the USA. During this process, it kept changing and widely affected our modern design and aesthetics. [1]

Masters in House

![bauhaus staff]()

When I read the Chinese version of The Bauhaus Group: Six Masters of Modernism [18], I saw other sides of those masters who created a new wave of design movement in the early 20th century. I realized that they all had their own belief and personality. The Bauhaus “internal” path was not at all as smooth as we could imagine. What amazed me was their collaboration in building the Bauhaus utopia. Even though they were all giants in their fields, they all served a greater purpose: art enlightenment. This openness of artists’ teamwork truly moved me. Working with others, sharing ideas, not fear of losing credit would happen when the whole team valued growing together and becoming better. The timelessness of Bauhaus was a testament to their achievement.

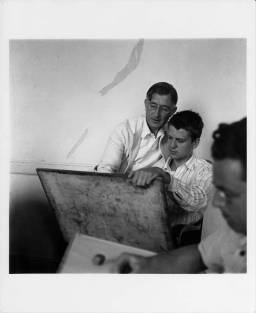

Paul Klee

Reading the book of The Bauhaus: Masters and Students by Themselves [2], I became very fond of Paul Klee’s works. Since the Bauhaus contained a wide range of styles and values, I chose to study Paul Klee’s art and do a formal breakdown of his work.

Klee said, “A drawing is simply a line going for a walk.” [3] In Klee’s art, I saw an “untutored simplicity”[9]. This might be a result of his admiration for children’s “positive wisdom” [10]. “The more helpless these children are, the more instructive their art, for even at this stage there is corruption ‐ when children start to absorb, or even imitate, developed works of art, ” he once said.[10] He tried to break the traditional rules constantly. He didn’t want to have any anticipation or presumption in his creating process. He wanted to stay free and discover things along the way.

Indeed, I always thought that his work is poetic. As I read his book did I recall that when I was a very little kid, it was his painting that I pointed at a music note in it and sang to my parent. I knew nothing about him or that image at that time. But I felt it. Then I read about his theory of “active lines” and “passive planes” in the book[3], I could still feel the same individual behind it – to me, his works were happy, carefree melodies. Therefore, I was not surprised to know that he was also a musician. He played violin to a professional level, yet his father, a music teacher, always encouraged his passion in art. He was a gifted and diligent artist who naturally related drawing to music. He often practiced the violin as a warm up for painting.[7] From 1921 to 1924/25 in Weimar, Klee taught classes in elemental design theory as part of the preliminary course. [8] In his Bauhaus lecture, he even compared the visual rhythm in drawings to the structural, percussive rhythms of a musical composition by the master of counterpoint, Johann Sebastian Bach. And yes, he succeeded in doing so.[7]

Klee said, “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” [3] Klee tried to reveal his vision. As a Modern master, he said, “formerly we used to represent things visible on earth, things we either liked to look at or would have liked to see. Today we reveal the reality that is behind visible things, thus expressing the belief that the visible world is merely an isolated case in relation to the universe and that there are other, more latent realities…”[11] But how to make the unseen seen? “Klee challenged traditional boundaries separating writing and visual art by exploring a new expressive, and largely abstract or poetic language of pictorial symbols and signs.”[12] That’s why I still remembered a music note in his painting. He used symbols as a language to describe his poem or song; but he used the symbols so simple that even a child could spot them out. I believe this was one of his ways to reveal something invisible to us. But were those jargons? He did not shout out any definition of his vision if he only used abstract symbols. He might be hiding, or he was simply open to any explanation that the viewers would have. He delivered a vague situation for the audience to experience. I believe this was another reason that his works stayed expressive and provoked interaction.

On the other hand, Martin Heidegger commented Klee’s work that something never seen before was visible in these paintings.[13] This might be another way to make the unseen visible. Klee once said, “Art should be like a holiday: something to give a man the opportunity to see things differently and to change his point of view.” [6]

What were those things never seen before? Well, here I found some other comments on Klee’s works.

“Klee’s career was a search for the symbols and metaphors that would make this belief visible. More than any other painter outside the Surrealist movement (with which his work had many affinities – its interest in dreams, in primitive art, in myth, and cultural incongruity), he refused to draw hard distinctions between art and writing. Indeed, many of his paintings are a form of writing: they pullulate with signs, arrows, floating letters, misplaced directions, commas, and clefs; their code for any object, from the veins of a leaf to the grid pattern of Tunisian irrigation ditches, makes no attempt at sensuous description, but instead declares itself to be a purely mental image, a hieroglyph existing in emblematic space. So most of the time Klee could get away with a shorthand organization that skimped the spatial grandeur of high French modernism while retaining its unforced delicacy of mood. Klee’s work did not offer the intense feelings of Picasso’s, or the formal mastery of Matisse’s.The spidery, exact line, crawling and scratching around the edges of his fantasy, works in a small compass of post-Cubist overlaps, transparencies, and figure- field play-offs. In fact, most of Klee’s ideas about pictorial space came out of Robert Delaunay’s work, especially the Windows. The paper, hospitable to every felicitous accident of blot and puddle in the watercolor washes, contains the images gently. As the art historian Robert Rosenblum has said, ‘Klee’s particular genius [was] to be able to take any number of the principal Romantic motifs and ambitions that, by the early twentieth century, had often swollen into grotesquely Wagnerian dimensions, and translate them into a language appropriate to the diminutive scale of a child’s enchanted world.‘

“If Klee was not one of the great form-givers, he was still ambitious. Like a miniaturist, he wanted to render nature permeable, in the most exact way, to the language of style – and this meant not only close but ecstatic observation of the natural world, embracing the Romantic extremes of the near and the far, the close-up detail and the “cosmic” landscape. At one end, the moon and mountains, the stand of jagged dark pines, the flat mirroring seas laid in a mosaic of washes; at the other, a swarm of little graphic inventions, crystalline or squirming, that could only have been made in the age of high-resolution microscopy and the close-up photograph. There was a clear link between some of Klee’s plant motifs and the images of plankton, diatoms, seeds, and micro-organisms that German scientific photographers were making at the same time. In such paintings, Klee tried to give back to art a symbol that must have seemed lost forever in the nightmarish violence of World War I and the social unrest that followed. This was the Paradise-Garden, one of the central images of religious romanticism – the metaphor of Creation itself, with all species growing peaceably together under the eye of natural (or divine) order.“- From Robert Hughes, “The Shock of the New” [4]

Now let us look at some art.

Formal Analysis of Paul Klee’s Work Senecio (An old man)

![Senecio, Paul Klee, 1922, oil on gauze, Kunstmuseum Basel, Basel]()

Shape & Line

We see many lines, either hard contours or edges of colors. A big circle, triangles, ellipses and rectangles depict the subject – a human. Proportions are way off. With the face being divided into two halves, basic geometric shapes lay out unsymmetrically. Two halves of the face look unbalanced. Because of the nose shape happening on the left side, we can almost guess that the two halves are separate sides of the face ( This reminds me of Picasso’s works that reveal all the hidden aspects of a figure at the same time ). Lines join together to create eye stopping points. We see shapes mainly divided by flat colors. The lips are abstracted into two squares. The left brow forms a sharp triangle while the right brow remains a smooth curve. Their difference creates different rhythms on the two parts of the face. Apart from the centered eye area, we generally see lines in vertical and horizontal directions, which is overall unified.

Color & Value

![Screen Shot 2015-04-20 at 11.59.17 PM]()

![Screen Shot 2015-04-20 at 11.59.17 PM]()

Primary warm colors, red, yellow and white, take the lead. We see pink, purple and orange colors too. Colors do not respond to value changes. Values do not respond to light and volume changes. However, the right side’s yellow is higher in saturation and brightness than the left one’s; the orange down below head is less saturated and darker than the upper area background. Also, the value palette shows that there is only one or two darker hues. It is very much possible that Klee uses value to separate colored shapes. High contrast colors accentuate the playfulness of his patterns.

Texture

We see texture of rough brushworks everywhere except for the pupil areas. In the pupils, we see flat rouge. Also, the eye and eyebrow areas have line contours. They are connected, leaning towards one side. Their content density creates our focus.

Character Design

As the saying goes, imitation is the highest form of flattery. After studying the Bauhaus story and ideal as well as Paul Klee’s work, I fell in love with the Bauhaus age. It had its limit, yet so full of youth and vigor. How I wish to go back to the Bauhaus “golden 10 years” (1923-1933) to witness the masters’ glory. However, time flies only forward. Today, when I look at the master’s work, there is something I can do more than merely looking at the beautiful surface of the final product. I did formal analysis and guessed his process, pretending that I would have been one of his students in the Bauhaus workshop. Hence, when I create something in the master’s style, instead of simply mirroring what I see, I can explain what I do.

Now I am designing characters based on the Bauhaus ideals after studying Paul Klee’s vision of form and color.

Paul Klee also made some puppets for his son. When making my designs, I looked at some images from this book below. “The artist neither counts them as a component of his oeuvre, nor does he list them in his catalogue raisonné. Thirty of the preserved puppets are stored at the Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern. ” [5]

![Paul Klee Hand Puppets Edited by Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern, Foreword by Andreas Marti, Texts by Christine Hopfengart, Aljoscha Klee, Felix Klee, Osamu Okuda, Tilman Osterwold, Eva Wiederkehr Sladeczek English 2007. 152 pp., 182 ills., 86 in color 23.00 x 26.60 cm hardcover ISBN 978-3-7757-1740-3]()

I want to mix those element with geometric shapes and flat colors. Going after Paul Klee’s belief, I will intentionally mimic children’s artwork. When composing my lines and colors, I will connect ambiguous shapes and forms with minimal details. Applying textures to those simple, crisp shapes will result in a collage-like style, which is a lovely trick for eyes that the modern digital media can make. In this sense, I respond to the tech reality of my age, the digital media.

Here are my character designs of a male figure and a female figure:

![Character Design by Yunxia 2015]()

How my design reflects my knowledge and their ideas:

![Design comment by Yunxia]()

Bibliography

1. William Smock, “The Bauhaus Ideal: Then and Now”, Academy Chicago Publishers, 2004

2. Frank Whitford, The Bauhaus: Masters and Students by Themselves, October 1, 1993

3. Klee and his teaching notes(Chinese Edition) (Chinese) Paperback, Chongqing University Press Pub. Date :2011-6-1, January 1, 2000

4. http://www.artchive.com/artchive/K/klee.html

5. Daniel Kupper: Paul Klee. p. 81

6. As quoted in the film Der Bauhaus, produced by TV-Rechte in Germany (1975)

7. Andrew Kagan, Paul Klee: Art and Music , Cornell Univ Press, 1983

8. http://bauhaus-online.de/en/atlas/personen/paul-klee

9. Paul Klee, On Modern Art , Faber & Faber, 1966

10. Susanna Partsch, Klee 1879 ‐ 1940 , Taschen, 1999. p 17

11. Fred Kleiner, Gardner’s Art Through the Ages: A Global History, Volume 2 , Clark Baxter, 2009. p 948

12. Rocky Mountain, Conference on Comics and Graphic Novels , Denver, CO, June 2012. p. 2

13. Watson, Stephen H., Heidegger, Paul Klee, and the Origin of the Work of Art , Academic journal article from The Review of Metaphysics, Vol. 60, No. 2

14. Art in Theory: 1900-1990, An Anthology of Changing Ideas, ed. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, pp. 338-343

15. Paul Klee – Making the Visible, Nedaa Elias, January 22, 2014

16. http://www.bauhaus-dessau.de/bauhaus-1919-19333.html

17. http://www.bauhaus-dessau.de/dessau-period-1925-1932.html

18. Nicholas Fox Weber, The Bauhaus Group: Six Masters of Modernism,ISBN:9787111409199,Jixiegongye Press Pub. Date: April 1st, 2013

__________

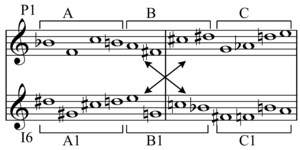

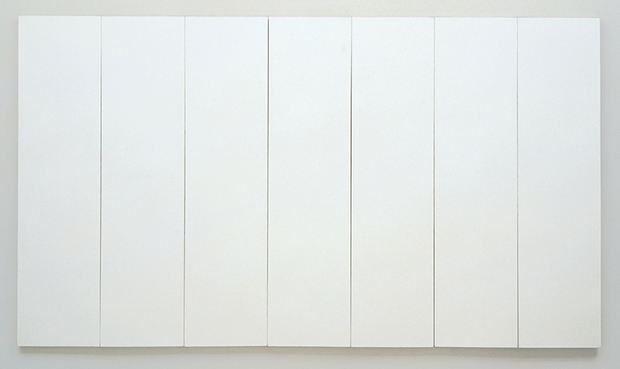

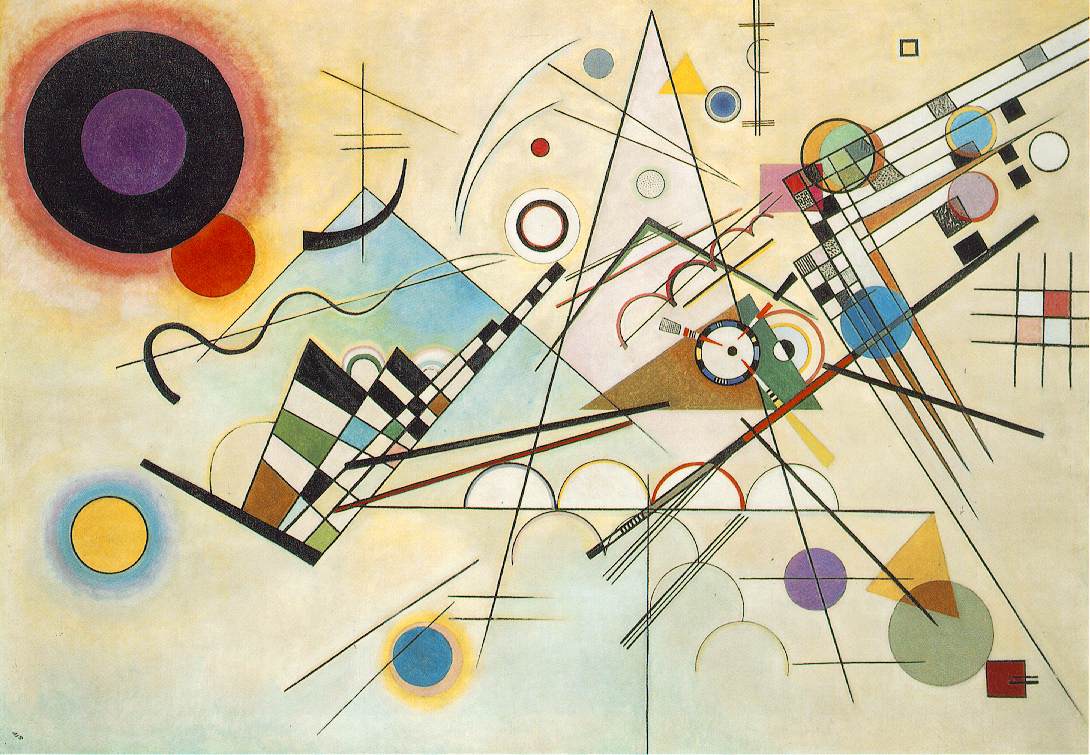

Composition VIII

1923

![]()

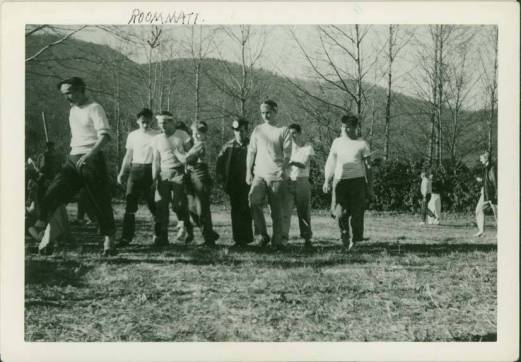

Black Mountain College

Uploaded on Apr 18, 2011

Class Project on Black Mountain College for American Literature

The pessimism of modern man comes from the realization that there is no “universal system” that can explain everything. Man with himself at the center of the universe cannot explain the world and how it got here, or even man and his place in it. Today, knowledge has become relative. The relativity of knowledge allows for many perspectives. Many people can have different views, without there being a “right” or “wrong” view. Many different views are just many different views, many different concepts, theories, ideas, systems, none are right or wrong–they are just different.![Pdvd_000 Pdvd_000]()

In a culture we see the same “relative” approach to concepts, styles, morals, views, some competing, some supporting but none are better or worse than any other. This “relativity” emphasizes disconnection and chaos not coherence, connectivity, and order. How did we get to this point? How did so much of the world come to have these beliefs about pessimism and relativism?

If the “Age of Nonreason” was the recognition of man’s pessimism and his resulting flight into absurdity, then, the “Age of Fragmentation” represents the modes of communication of that pessimism and Nonreason. Rather than a philosophy, the Age of Fragmentation is really the story of how modern pessimism has been propagated geographically, culturally and socially to almost all mankind.

Schaeffer opens this chapter of How Should We Then Live with the following statement: “Modern pessimism and modem fragmentation have spread in three distinct ways across to people of our own culture and to people worldwide. Geographically, it spread from the European mainland to England, after a time jumping the Atlantic to the United States. Culturally, it spread in the various disciplines from philosophy to art, to music, to general culture (the novel, poetry, drama, films), and to theology. Socially, it spread from the intellectuals to the educated and then through the mass media to everyone.” It is primarily in the culture, through its art, music, literature, and drama/films that man comes to learn how sees and understands himself. It is in the output of modern culture that the humanist’s soul is revealed. As we consider the “Age of Fragmentation” consider the statement that “As a man thinketh, so is he.”

The social spread of modern pessimism introduced a phenomenon that has been called the “generation gap.” The generation gap came about as the younger generations were introduced to new thoughts and ideas while their elders still held the “old” ways. Those who held the old ways did so more from habit than conviction. They were without a foundation for the values they claimed to hold so dear. With the recognition by the younger generation that there was no basis for the beliefs that their elders held, a gap in belief systems of the generations appeared. Dead traditions, empty values, force of habit, described the older generation while change, new thinking, pessimism in reason, optimism in Nonreason, became the foundation for the values of the younger generation. Welcome to the generation gap.

Today, Western Culture has almost reached what Schaeffer calls a “monolithic consensus.” The overwhelming consensus is the basic dichotomy of humanism–-reason leads to pessimism and optimism is in the area of Nonreason. This view was first taught in philosophy, then it was presented in art, music, literature, and drama/film, seeping throughout the culture, eventually even into theology–-Welcome to the Age of Fragmentation!

How did art come to be used as a vehicle for modern thought? Art in general and painting in particular has always seemed to represent the thought of the day. It is one thing to read about the thought of a particular period but the thought comes alive when one looks at the art of the period. It was no different with modern thought and its wrestling with the “dichotomy of humanism” and modern art. As Schaeffer explains, the way to modern art began in response to “the way naturalists were painting.” The naturalist painters could replicate the scene which they were painting but the viewer was left to ask the question “Is there any meaning to what I am looking at?” And on reflection the answer was no because the “art had become sterile.” This began to change with the rise of Impressionism.

Impressionism was a major movement, first in painting and later in music, that developed primarily in France during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Impressionist painting comprises the work produced between about 1867 and 1886 by a group of artists who shared a set of related approaches and techniques. The most conspicuous characteristic of Impressionism was an attempt to accurately and objectively record visual reality with transient effects of light and color. The principal Impressionist painters were Claude Monet, Pierre Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, Alfred Sisley, Berthe Morisot, Armand Guillaumin, and Frédéric Bazille, who worked together, influenced each other, and exhibited together independently. Edgar Degas and Paul Cézanne also painted in an Impressionist style for a time in the early 1870s.

The period of Impressionism and Postimpressionism painting was about appearance and reality. There were no universals in impressionistic painting. The Impressionist painters were all great artists yet their works leave unanswered the question “where is the reality?” “These men painted only what their eyes brought them, but this left the question whether there was a reality behind the light waves reaching the eyes.”

Claude Monet’s Haystack series of 1890-1891 provide us with something of a bridge between the impressionist and postimpressionist painters. The series did not function as an accurate record of sequence of time nor as a row of stacks of wheat. Instead, asMonet told Geffroy, he was “more and more driven with the need to render ce que j’epreuve”—what he felt or experienced as he encountered the world of nature. And he came to experience nature differently. “For me, landscape hardly exists at all as landscape, because its appearance is constantly changing,” he said; “but it lives by virtue of its surroundings—the air and light—which vary continually.” A single painting of the subject denies this constant variation over time. So what Monet pursued was not the objective fact of these stacks of grain, as defined by light and air, but how his eye perceived them over the passage of time. The landscape served, then, as a point of departure, a vehicle for artistic self-expression. Monet’s series is testimony to one of the basic tenets of modern art: the notion that the artist can reconstruct nature according to the formal and expressive potential of the image itself. One might suggest that here reality became a dream. “As reality tended to become a dream, Impressionism as a movement fell apart. With Impressionism the door was opened for art to become the vehicle for modern thought.”

Postimpressionism is an umbrella term that encompasses a variety of artists who were influenced by Impressionism but took their art in other directions. The postimpressionist period lasts from 1880 to the 1900. There is no single well-defined style of Postimpressionism, but in general it is less idyllic and more emotionally charged than Impressionist work. The classic postimpressionists are Paul Gauguin, Paul Cezanne, Vincent van Gogh, Henri Rousseau and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. The Pointillists and Les Nabis are also generally included among the Postimpressionists.

Breaking free of the naturalism of Impressionism in the late 1880s, this group of young painters sought independent artistic styles for expressing emotions rather than simply optical impressions, concentrating on themes of deeper symbolism. By using simplified colors and definitive forms, their art was characterized by a renewed aesthetic sense as well as abstract tendencies. The postimpressionist painters, responding to Impressionism, followed diverse stylistic paths in search of authentic intellectual and artistic achievements. These artists, often working independently, are today called postImpressionists. These postimpressionists attempted to find the way back to reality, to the absolute behind the particulars. “They felt the loss of universals, tried to solve the problem, and they failed. It is not that these painters were always consciously painting their philosophy of life, but in their work as a whole, their worldview was often reflected.” The art of the great postimpressionists “became the vehicle for modern man’s view of the fragmentation of truth and life.”

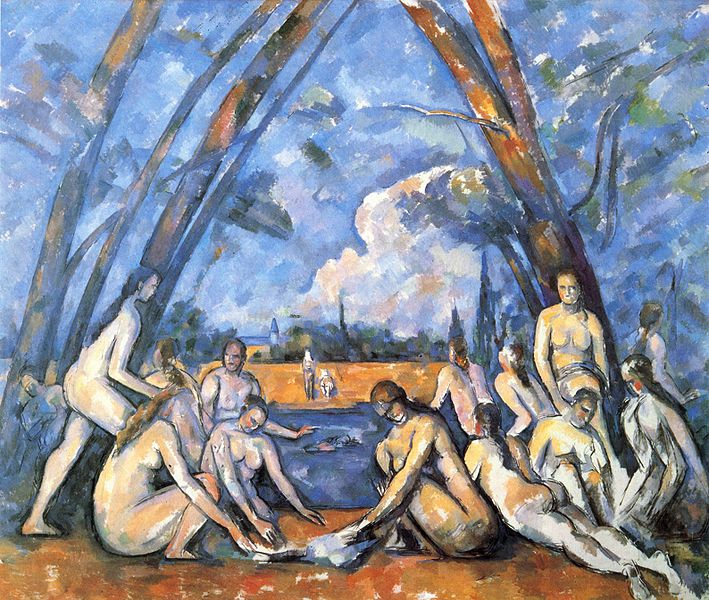

For Francis Schaeffer, painting reflected philosophy. “As philosophy had moved from unity to a fragmentation, this fragmentation was also carried into the field of painting. The fragmentation shown in postimpressionist paintings was parallel to the loss of a hope for a unity of knowledge in philosophy.” For example Paul Cezanne, expressing his worldview, reduced nature to what, he considered its basic geometric forms. “In this he was searching for a universal which would tie all kinds of particulars in nature together. Nonetheless, this gave nature a fragmented, broken appearance.” Schaeffer sees this fragmentation in one of Cezanne’s better-known works Bathers (©1905). Cezanne painted many pictures with bathers, including nmany compositions of male and female bathers, singly or in groups. “However, in this painting Cézanne brought the appearance of fragmented reality not only to his painting of nature but to man himself. Man, too, was presented as fragmented.” There was a parallel search for the “universal in art as well as in philosophy.”

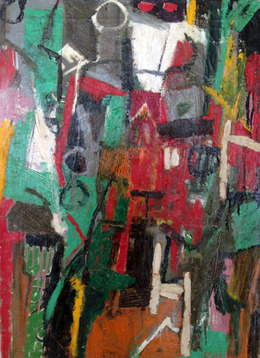

Painting expresses an idea as a work of art. From this point art could move to the extremes of ultranaturalism, such as the photo-realists or to abstraction, where “reality becomes so fragmented that it disappears, and man is left to make up his personal world.” Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), a Russian-born artist was one of the first creators of pure abstraction in modern painting.

Kandinsky was never solely a painter, but a theoretician, and organizer at the same time. A gifted author, he expressed his views on art and artistic activity in his numerous writings. After successful avant-garde exhibitions, he founded the influential Munich group Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider; 1911-14) and began completely abstract painting. His forms evolved from fluid and organic to geometric and, finally, to pictographic (e.g. Tempered Élan, 1944).

Besides painting and writing, Kandinsky, was an accomplished musician. He once said: “Color is the keyboard, the eyes are the harmonies, the soul is the piano with many strings. The artist is the hand that plays, touching one key or another, to cause vibrations in the soul.” The concept that color and musical harmony are linked has a long history, intriguing scientists such as Sir Isaac Newton. Kandinsky used color in a highly theoretical way associating tone with timbre (the sound’s character), hue with pitch, and saturation with the volume of sound. He even claimed that when he saw color he heard music. In 1912 Kandinsky wrote an article titled “About the Question of Form” in The Blue Rider saying that, “since the old harmony (a unity of knowledge) had been lost, only two possibilities remained–extreme naturalism or extreme abstraction.” “Both,” he said, “were equal.”

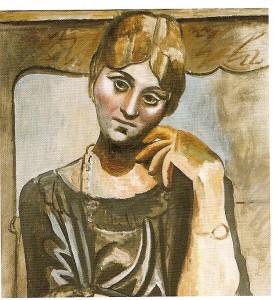

Pablo Picasso’s (1881-1973) painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon is a significant work in the genesis of modern art. The painting portrays five naked prostitutes in a brothel; two pushing aside curtains around the space where the other women strike seductive and erotic poses—but their figures are composed of flat, splintered planes rather than rounded volumes, their eyes are lopsided or staring or asymmetrical, and the two women at the right have threatening masks for heads. The space, too, which should recede, comes forward in jagged shards, like broken glass. In the still life, at the bottom, a piece of melon slices the air like a scythe.

The faces of the figures at the right are influenced by African masks, which Picasso assumed had functioned as magical protectors against dangerous spirits: this work, he said later, was his “first exorcism painting.” A specific danger he had in mind was life-threatening sexual disease, a source of considerable anxiety in Paris at the time; earlier sketches for the painting more clearly link sexual pleasure to mortality. In its brutal treatment of the body and its clashes of color and style (other sources for this work include ancient Iberian statuary and the work of Paul Cézanne), Les Demoiselles d’Avignon marks a radical break from traditional composition and perspective.

The result of months of preparation and revision, this painting revolutionized the art world when first seen in Picasso’s studio. Its monumental size, 8′ x 7′ 8″, underscored, “the shocking incoherence resulting from the outright sabotage of conventional representation.” Picasso drew on sources as diverse as Iberian sculpture, African tribal masks, and El Greco’s painting to make this startling composition.

In great art the technique fits the worldview being presented, and fragmentation or abstraction well fits the worldview of modern man. The technique expresses both “the concept of a fragmented world and fragmented man.” A world-famous photographer and writer, David Douglas Duncan, a friend of Pablo Picasso, about whom he published six coffee-table books, “says about a certain set of Picasso’s pictures in Picasso’s private collection is in a way a summing up of much of Picasso’s work: ‘Of course, not one of these pictures was actually a portrait but his prophecy of a ruined world.”“ Abstract art “was a complete break with the art of the Renaissance which had been founded on man’s humanist hope.” We saw In Les Demoiselles d’Avignon people were no longer human: “the humanity had been lost.” This becomes increasingly apparent that the techniques of art become more advanced “humanity was increasingly fragmented.” Fragmentation and abstraction, in art, was a wide road to “the absurdity of all things.”

Dada was an informal international movement that began with the start of the First World War. Primarily, in Europe and North America, Dada was an antiwar movement, “a protest against the bourgeois nationalist and colonialist interests which many Dadaists believed were the root cause of the war, and against the cultural and intellectual conformity—in art and more broadly in society—that corresponded to the war.” Most Dadaists believed that “the ‘reason’ and ‘logic’ of bourgeois capitalist society had led people into war. They expressed their rejection of that ideology in artistic expression that appeared to reject logic and embrace chaos and irrationality.” For example, George Grosz later recalled that his Dadaist art was intended as a protest “against this world of mutual destruction.”

Dadaists rebelled against what modern society and culture were. Dada was not art. It was anti-art. “According to its proponents, Dada was not art—it was ‘anti-art’ in the sense that Dadaists protested the contemporary academic and cultured values of art.” The intent of Dada was to “destroy traditional culture and aesthetics.” The Dada movement, more than an antiwar protest movement, popularized the absurd, not simply in art but in everything. Schaeffer concludes: “Dada carried to its logical conclusion the notion of all having come about by chance; the result was the final absurdity of everything, including humanity.”

Schaeffer concludes this section of art as a vehicle of Modern Thought by reviewing the progression of philosophical thought and its interweaving with art. “the philosophers from Rousseau, Kant, Hegel and Kierkegaard onward, having lost their hope of a unity of knowledge and a unity of life, presented a fragmented conception of reality; then the artists painted that way. It was the artist, however, who first understood that the end of this view was the absurdity of all things.” This is the way “the concept of fragmented reality spread in the twentieth century. The philosophers first formulated intellectually what the artists later depicted artistically.”

Perhaps the most widely popular method of spreading the message of modern thought has been music. Schaeffer believes Beethoven and his The Last Quartets were the doorway to modern music. The influence of the “quartets” was obvious in the two streams of classical music that evolved from them: the German and the French. Beethoven’s influence is seen in those that followed him: Wagner, Mahler and Schoenberg.

It is with Arnold Schoenberg’s (1874–1951) that we come into the music which became the “vehicle for modern thought.” Schoenberg, an Austrian and later American Composer, is “associated with the expressionist movements in early 20th-century German poetry and art, and he was among the first composers to embrace atonal motivic development.” Schoenberg was best known for his twelve-tone technique. The compositional technique involving tone rows was a rejection of the past tradition in music. Schaeffer tells us: “This was ‘modern’ in that there was perpetual variation with no resolution.” Schaeffer highlights the difference in resolution between Bach and Schoenberg. Schoenberg’s music with no resolution “stands in sharp contrast to Bach who, on his biblical base, had much diversity but always resolution. Bach’s music had resolution because as a Christian he believed that there will be resolution both for each individual life and for history. As the music which came out of the biblical teaching of the Reformation was shaped by that worldview, so the worldview of modern man shapes modern music.”

Claude Debussy (1862-1918) was the most important French composer of the early twentieth century. As Schaeffer suggests “His direction was not so much that of nonresolution but of fragmentation.” Debussy’s importance comes in that he “opened the door to fragmentation in music and influenced most composers since, not only in classical music but in popular music and rock as well. Even the music that is one of the glories of America–black jazz and black spirituals–was gradually infiltrated.”

The fragmentation in music is parallel to the fragmentation which occurred in painting. The fragmentation in music and in painting were not only changes in techniques but an expression of the worldview of the artists and in turn brought this worldview to people throughout the world. Art and music brought a worldview of fragmentation and abstraction to people who would never have opened a book of philosophy, or would have had any interest in a “worldview.” Popular music beginning with some elements of rock in the 60s carried its message of fragmentation to the young people of the world. Music has become the universal language of the world and with it, this message of fragmentation and abstraction.

Besides music and painting, poetry, drama, literature, and films have also carried these ideas to the world. With the coming of the internet and world communications the message has become one that continually bombard us-–“shouting at us a fragmented view of the universe and of life.” The most successful vehicle for proclaiming the message of fragmentation came in films. Schaeffer observes: “The important concepts of philosophy increasingly began to come not as formal statements of philosophy but rather as expressions in art, music, novels, poetry, drama, and the cinema.” As our culture becomes more visual we see (pun intended) more and more “major philosophic statements . . . made through films.” Philosophers are no longer found in academe, today. They are more likely found directing or producing movies with “a message.” And more than likely the message is “absurd, ” abstract and fragmented.

What do the movies “the Deer Hunter,” “The Departed,” “Midnight Cowboy,” “Unforgiven,” “American Beauty,” and “Silence of the Lambs” share? Yes, they won an academy award for Best Picture–-but what was the message that they conveyed to their worldwide audiences? What is the purpose of adult movie such as “Golden Compass” being advertised as a child’s movie? And we have not even addressed television! Seven days a week, twenty-four hours a day we are overloaded with a humanistic worldview. A worldview that is without hope, without answers, and is becoming more and more absurd. Schaeffer warns: “Modern people are in trouble indeed. These things are not shut up within the art museums, the concert halls and rock festivals, the stage and movies, or the theological seminaries. People function on the basis of their worldview.” Is there any wonder “that it is unsafe to walk at night through the streets of today’s cities?” “As a man thinketh, so is he.”

_________

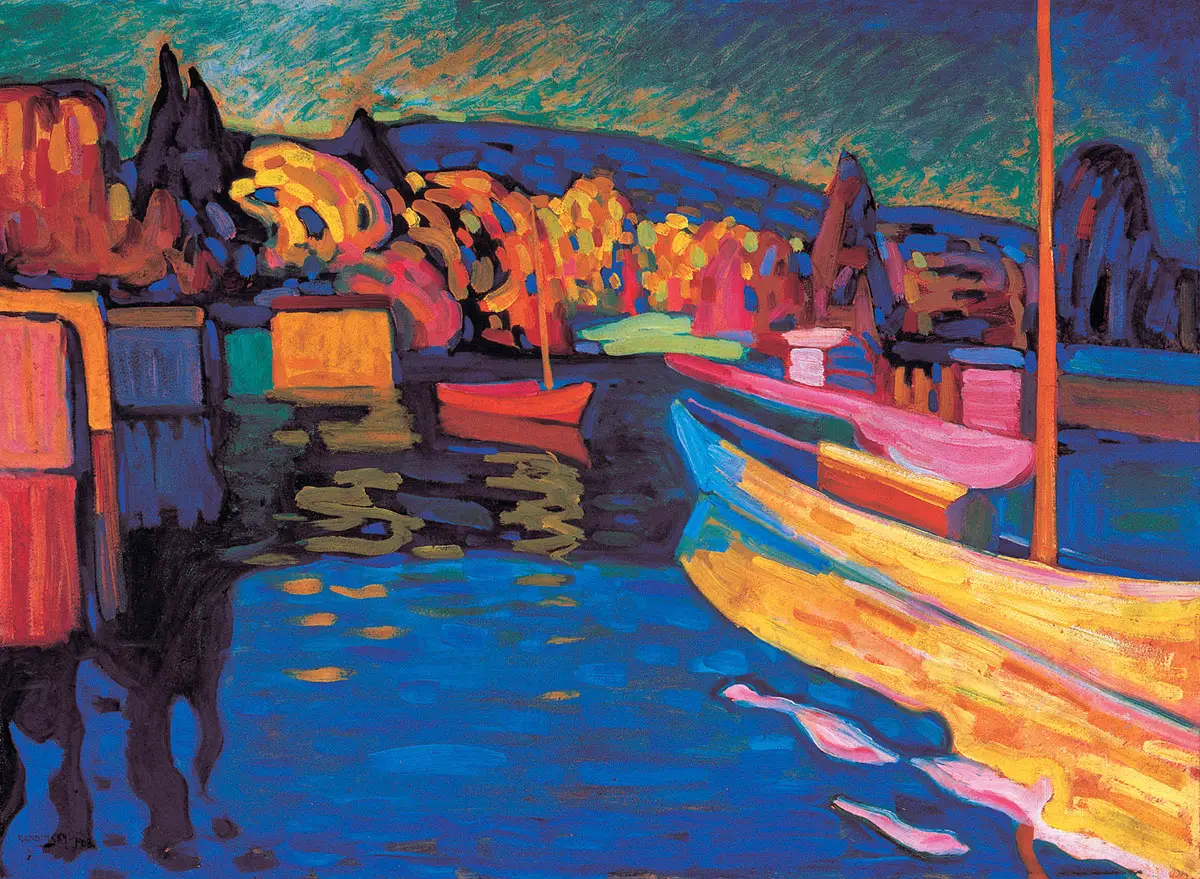

Autumn Landscape with Boats, 1908

![]()

Copyright © 2002. Modernism Magazine.

I found the Bauhaus movement very interesting and the article above even noted:

The leading role of the Bauhaus, such as Walter Gropius, Oskar Schlemmer, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Xanti Schawinsky, Paul Klee, Wasily Kandinsky experimented synthesis among human, space and machine not only in their own area, but also on the stage. They believed that their research about mechanical and abstract stage design, costume, doll, dance, humorous movement, light and sound could even make a change of the modern human body and mind.

What exactly were some of these artists attempting to do and why does this statement finish with the bold assertion “could even make a change of the modern human body and mind”?

Let me tell you what Wasily Kandinsky (who was seen in the film THE LONGEST RIDE) and Paul Klee were attempting to do. They wanted to make a connection with art and find a word of direction from art from their lives. They were secular men so they were not looking for any spiritual direction from a personal God. However, the Bible clearly notes that God exists and we all know He is there. Romans Chapter one asserts, “For that which is KNOWN about God is EVIDENT to them and MADE PLAIN IN THEIR INNER CONSCIOUSNESS, because God has SHOWN IT TO THEM…” (Romans 1:19).

Every person has this inner conscious that is screaming at them that God exists and that is why so many of the sensitive men involved in art have been looking for a message to break forth. Here we see something similar with the life and quest of the artist Paul Klee. I read on January 15, 2007 the blog post “Strolling Through Modern Art,” and I wanted to share a portion of that post:

![]()

This particular drawing came to mind while I was looking at the Art Institute of Chicago’s website and I came across some artwork by Joan Miro, who is exhibited at AIC. Vee Mack’s drawings generally demonstrate better draughtsmanship than this drawing displays but I thought that the concept was amusing and the implied commentary worth considering. Are you a fan of Joan Miro, Piet Mondrian, Paul Klee, Jackson Pollock, Willem De Kooning and Wasily Kandinsky?What does this elderly gentleman think of his stroll through the paramecium of the artworld? Francis Schaeffer noted in “The God Who is There” that Paul Klee and similar artists, introduced the idea of artwork generated in a manner similar to how a Ouija Board generates words from outside the artist’s conscious intent. Schaeffer observed that Klee “hopes that somehow art will find a meaning, not because there is a spirit there to guide the hand, but because through it the universe will speak even though it is impersonal in its basic structure.” [page 90] Why would an impersonal universe have something to say? What does meaninglessness have to communicate? Schaeffer explains that “these men will not accept the only explanation which can fit the facts of their own experience, they have become metaphysical magicians. No one has presented an idea, let alone demonstrated it to be feasible, to explain how the impersonal beginning, plus time, plus chance, can give personality . . . As a result, either the thinker must say man is dead, because personality is a mirage; or else he must hang his reason on a hook outside the door and cross the threshold into the leap of faith which is the new level of despair.” [page 115]Vee Mack’s sketch demonstrates the paradox of an average man viewing images, which represent the nonsense of Dadaism and chaos. It is the overeducated who will look at something that is inherently meaningless and try to find deep meaning in it, while the average man sees it and observes with reasonable common sense that this or that is an absurd waste of time.By the way, while it may appear as though I am favoring one artist for these posts, I am not receiving the variety of artwork that I had hoped for from other artists and I happen to have ample access to much of Vee Mack’s unpublished portfolio. Therefore, until I receive other artwork, I will have to rely on what I have on hand.

Paul Klee

__________

Michael Gaumnitz : Paul Klee The Silence of the Angel (2005)

Published on Aug 17, 2013

PAUL KLEE: THE SILENCE OF THE ANGEL is a visual journey into the work of a major painter of the 20th century by Michael Gaumnitz, an award-winning documentarian of artists and sculptors. Like Kandinsky and Delaunay, Klee revolutionized the traditional concepts of composition and color.

![]()

Gropius with Béla Bartók and Paul Klee in 1927

![Willem de Kooning http://www.biography.com/people/willem-de-kooning-9270057]()

(1904-1997) Abstract Expressionist Painter, Sculptor

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/willem-de-kooning-1433

![Elaine de Kooning http://www.theartstory.org/artist-de-kooning-elaine.htm]()

(1918-1989) artist, art critic, portraitist and teacher.

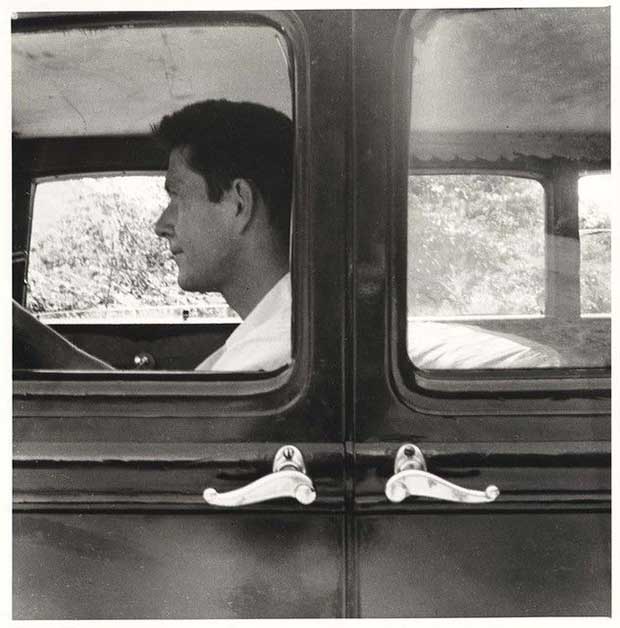

![Robert Rauschenberg Dmitri Kasterine]()

(1925-2008) Painter, sculptor, printmaker, photographer and performance artist

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/robert-rauschenberg-1815

![Cy Twombly American painter Cy Twombly at the Louvre museum in Paris. Twombly has died aged 83. Photograph: Christophe Ena/AP]()

(1928-2011) Painter, draughtsman, printmaker, sculptor.

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/cy-twombly-2079

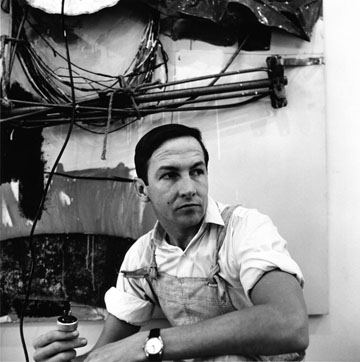

![John Cage photo: Susan Schwartzenberg]()

(1912-1992) composer, philosopher, poet, music theorist, artist, printmaker.

http://www.last.fm/music/John+Cage

![Buckminster Fuller Buckminster Fuller at Black Mountain College with models of geodesic domes, 1949 © Buckminster Fuller Institute]()

(1895-1983) Philosopher, designer, architect, artist, engineer, entrepreneur, author, mathematician, teacher and inventor

http://designmuseum.org/design/r-buckminster-fuller

![Annie Albers © 1947 Nancy Newhall. © 2003 The Estate of Beaumont Newhall and Nancy Newhall, Courtesy of Scheinbaum and Russek Ltd., Santa Fe, New Mexico]()

(1899- 1994) textile designer, weaver, writer and printmaker

http://www.albersfoundation.org/Albers.php?inc=Introduction

![Mary C Richards blackmtnbarb.blogspot.com]()

(1916-1999) Poet, Potter and writer

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/M._C._Richards

______

Good article:

“Of all the arts, abstract painting is the most difficult. It demands that you know how to draw well, that you have a heightened sensitivity for composition and for colors, and that you be a true poet. This last is essential.”

WASSILY KANDINSKY SYNOPSIS

One of the pioneers of abstract modern art, Wassily Kandinsky exploited the evocative interrelation between color and form to create an aesthetic experience that engaged the sight, sound, and emotions of the public. He believed that total abstraction offered the possibility for profound, transcendental expression and that copying from nature only interfered with this process. Highly inspired to create art that communicated a universal sense of spirituality, he innovated a pictorial language that only loosely related to the outside world, but expressed volumes about the artist’s inner experience. His visual vocabulary developed through three phases, shifting from his early, representative canvases and their divine symbolism to his rapturous and operatic compositions, to his late, geometric and biomorphic flat planes of color. Kandinsky’s art and ideas inspired many generations of artists, from his students at the Bauhaus to the Abstract Expressionists after World War II.

WASSILY KANDINSKY KEY IDEAS

Painting was, above all, deeply spiritual for Kandinsky. He sought to convey profound spirituality and the depth of human emotion through a universal visual language of abstract forms and colors that transcended cultural and physical boundaries.

Kandinsky viewed non-objective, abstract art as the ideal visual mode to express the “inner necessity” of the artist and to convey universal human emotions and ideas. He viewed himself as a prophet whose mission was to share this ideal with the world for the betterment of society.

Kandinsky viewed music as the most transcendent form of non-objective art – musicians could evoke images in listeners’ minds merely with sounds. He strove to produce similarly object-free, spiritually rich paintings that alluded to sounds and emotions through a unity of sensation.

___________________

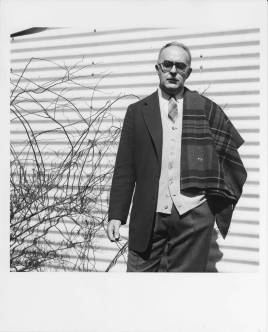

Francis Schaeffer pictured below

![]()

_________________

Here are some comments from Francis Schaeffer (includes two quotes from David Douglas Duncan) from the episode “The Age of Fragmentation” which is part of the film series HOW SHOULD WE THEN LIVE?

Cezanne reduced nature to what he considered its basic geometric forms. In this he was searching for an universal which would tie all kinds of individual things in nature together, but this gave a broken fragmented appearance to his pictures.

________________________________

In his bathers there is much freshness, much vitality. An absolute wonder in the balance of the picture as a whole, but he portrayed not only nature but also man himself in fragmented form.

I want to stress that I am not minimizing these men as men. To read van Gogh’s letters is to weep for the pain of this sensitive man. Nor do I minimize their talent as painters. Their work often has great beauty indeed. But their art did become the vehicle of modern man’s view of fractured truth and light. As philosophy had moved from unity to fragmentation so did painting.

From this point onward one could either move to the extreme of an ultranatural naturalism, such as the photo-realists, or to the extreme of freedom, whereby reality becomes so fragmented that it disappears, an man is left to make up his own personal world. In 1912 abstract Expressionist painter Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) wrote an article entitled “About the Question of Form” in THE BLUE RIDER saying that , since the old harmony (a unity of knowledge) had been lost, only two possibilities remained–extreme naturalism or extreme abstraction. Both, he said, were equal.

Gertrude Stein (1874-1946), an American author living in Paris, was important at this time. It was at her home that many artists and writers met and talked of these things, hammering out in talk the new ideas–many of them long before they personally became famous. Picasso initially met Cezanne at her home.

With this painting modern art was born. Picasso painted it in 1907 and called it Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. It unites Cezzanne’s fragmentation with Gauguin’s concept of the noble savage using the form of the African mask which was popular with Parisian art circle of that time. In great art technique is united with worldview and the technique of fragmentation works well with the worldview of modern man. A view of a fragmented world and a fragmented man and a complete break with the art of the Renaissance which was founded on man’s humanist hopes.

Here man is made to be less than man. Humanity is lost. Speaking of a part of Picasso’s private collection of his own works David Douglas Duncan says “Of course, not one of these pictures was actually a portrait, but his prophecy of a ruined world.”

I want you to understand that I am not saying that gentleness and humanness is not present in modern art, but as the techniques of modern art advanced, humanity was increasingly fragmented–as we shall see, for example, with Marcel Duchamp The artists carried the ideo of a fragmented reality onto the canvas. But at the same time being sensitive men, the artists realized where this fragmented reality was taking man, that is, to the absurdity of all things. ….The opposite of fragmentation would be unity, and the old philosophic thinkers thought they could bring forth this unity from the humanist base and then they gave this (hope) up.

Hans Arp (1887-1966), an Alsatian sculptor, wrote a poem which appeared in the final issue of the magazine

De Stijl (The Style) which was published by the

De Stijl group of artists led by Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg. Mondrian (1872-1944) was the best-known artist of this school. He was not of the Dada school which accepted and portrayed absurdity. Rather, Mondrian was hoping to paint the absolute. Hand Arp, however, was a Dadaist artist connected with

De Stijl. His power “Für Theo Van Doesburg,” translated from German reads:

the head downward

the legs upward

he tumbles into the bottomless

from whence he came

he has no more honour in his body

he bites no more bite of any short meal

he answers no greeting

and is not proud when being adored

the head downward

the legs upward

he tumbles into the bottomless

from whence he came

like a dish covered with hair

like a four-legged sucking chair

like a deaf echotrunk

half full half empty

the head downward

the legs upward

he tumbles into the bottomless

from whence he came

Dada carried to its logical conclusion the notion of all having come about by chance; the result was the final absurdity of everything, including humanity.

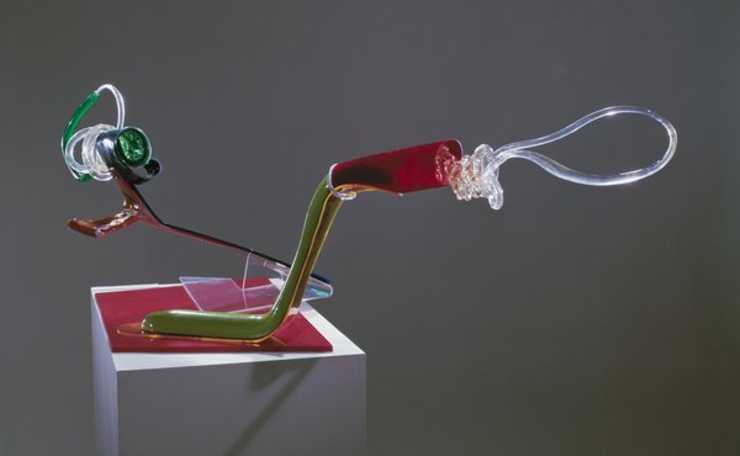

The man who perhaps most clearly and consciously showed this understanding of the resulting absurdity fo all things was Marcel Duchamp (1887-1969). He carried the concept of fragmentation further in Nude Descending a Staircase (1912), one version of which is now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art–a painting in which the human disappeared completely. The chance and fragmented concept of what is led to the devaluation and absurdity of all things. All one was left with was a fragmented view of a life which is absurd in all its parts. Duchamp realized that the absurdity of all things includes the absurdity of art itself. His “ready-mades” were any object near at hand, which he simply signed. It could be a bicycle wheel or a urinal. Thus art itself was declared absurd.

![stairs]()

![stool wheel]()

The historical flow is like this: The philosophers from Rousseau, Kant, Hegel and Kierkegaard onward, having lost their hope of a unity of knowledge and a unity of life, presented a fragmented concept of reality; then the artists painted that way. It was the artists, however, who first understood that the end of this view was the absurdity of all things. Temporally these artists followed the philosophers, as the artists of the Renaissance had followed Thomas Aquinas. In the Renaissance it was also philosophy, followed by the painters (Cimabue and Giotto), followed by the writers (Dante). This was the same order in which the concept of fragmented reality spread in the twentieth century. The philosophers first formulated intellectually what the artists later depicted artistically.” (187-190)

_______________

![Picasso and Olga Khokhlova Picasso and Olga Khokhlova]()

Their son Paulo (Paul) was born in 1921 (and died in 1975), influencing Picasso’s imagery to turn to mother and child themes. Paul’s three children are Pablito (1949-1973), Marina (born in 1951), and Bernard (1959). Some of the Picassos in this Saper Galleries exhibition are from Marina and Bernard’s personal Picasso collection.

![Pablo Picasso. Portrait of Paul Picasso as a Child.]()

Portrait of Paul Picasso as a Child. 1923. Oil on canvas.

Collection of Paul Picasso, Paris, France.

In 1917 ballerina Olga Khokhlova (1891-1955) met Picasso while the artist was designing the ballet “Parade” in Rome, to be performed by the Ballet Russe. They married in the Russian Orthodox church in Paris in 1918 and lived a life of conflict. She was of high society and enjoyed formal events while Picasso was more bohemian in his interests and pursuits. Their son Paulo (Paul) was born in 1921 (and died in 1975), influencing Picasso’s imagery to turn to mother and child themes. Paul’s three children are Pablito (1949-1973), Marina (born in 1951), and Bernard (1959). Some of the Picassos in this Saper Galleries exhibition are from Marina and Bernard’s personal Picasso collection.

![http://www.sapergalleries.com/PicassoOlga.jpg]()

![http://www.sapergalleries.com/PicassoOlgaPhoto.jpg]()

__________________________________

The Longest Ride (2015) • View trailer

3.5 stars. Rated PG-13, for sensuality, fleeting nudity, dramatic intensity and brief war violence

By Derrick Bang

You gotta hand it to Nicholas Sparks: He certainly knows what sells.

Ten films have been made from his novels, since 1999’s Message in a Bottle, and most have been well received: absolutely indisputable date-bait. No. 11, based on his novel The Choice, already is waiting in the wings for release next year.

|

Luke (Scott Eastwood) surprises Sophia (Britt Robertson) with a “dinner date” that’s

actually an early evening picnic at the edge of a gorgeous shoreline. Could anything be

more romantic? |

Some of the more recent big-screen adaptations, though, have suffered from a surfeit of predictable Sparks clichés: the too-precious, meet-cute encounters between young protagonists; rain-drenched kisses; the contrived tragedies; the wildly vacillating happy/sad shifts in tone. Indifferent directors and inexperienced leads haven’t helped, with low points awarded to Miley Cyrus’ dreadful starring role in 2010’s The Last Song, and the on-screen awkwardness of James Marsden and Michelle Monaghan, in The Best of Me.

Which makes The Longest Ride something of a relief, actually, because its stars — Scott Eastwood and Britt Robertson — share genuine chemistry. We eagerly anticipate their scenes together, in part because they occupy only a portion of their own film. In yet another Sparks cliché, this narrative’s other half belongs to an entirely different set of lovers, whose swooning courtship and marriage unfold half a century earlier, as recounted via — you guessed it — a box filled with old letters.

Sparks obviously can’t resist the impulse to cannibalize his own classic, The Notebook … which, come to think of it, also got re-worked in The Best of Me. Never argue with excess, I guess.

Anyway…

Transplanted big-city girl Sophia (Robertson), a senior majoring in modern art at North Carolina’s Wake Forest University, is inches away from graduation and an eagerly anticipated internship at a prestigious New York gallery. Romance is the last thing on the mind of this serious scholar, until she’s dragged to a bull-riding competition by best gal-pal Marcia (the adorably perky Melissa Benoist, who deserves her own starring role, and soon).

Inexplicably caught up in the suspense of these dangerous, eight-second battles between man and horned beast, Sophia can’t take her eyes off Luke (Eastwood). He’s a former champ on the comeback trail, following a disastrous accident, a year earlier, which left him with A Mysterious And Potentially Fatal Condition.

As is typical of such melodramatic touches, we never learn the exact nature of Luke’s affliction, only that he courts death — more than usual — every time he now gets on a bull. And that he pops pills, presumably pain pills, like peppermints.

Anyway…

Sophia and Luke have nothing in common, and yet they’re drawn together; a hesitant relationship blossoms, despite the certain knowledge that Sophia soon will depart for New York. These early scenes are charming: scripted simply but effectively by Craig Bolotin, and engagingly played by our two leads, who are quite good together. Sophia can’t resist Luke’s polite Southern gentility; frankly, neither can we.

Heading home late one rain-swept night, they come across a crashed car whose elderly driver, Ira Levinson (Alan Alda), is hauled from the wreck just in time … along with a box he begs Sophia to retrieve. Later, in the calm of the hospital where Ira begins his recovery, Sophia discovers that the box is filled with scores of his old love letters to Ruth, his deceased wife.

Ira’s condition is frail, his mental state approaching surrender. Perceiving that the letters bring solace to this old man, even though his eyesight isn’t up to the challenge of enjoying them himself, Sophia offers to read them aloud: a task she soon embraces on a daily basis.

(I’m not sure how Sophia finds the time for her studies, her relationship with Luke and her sessions with Ira … but there you go.)

And, thus, we’re swept back to the early 1940s, as a younger Ira (Jack Huston) meets and falls in love with Ruth (Oona Chaplin), a European Jewish refugee newly arrived in the States with her parents. Ira, besotted by this enchanting young woman, can’t believe that such a sophisticated beauty would spare a second glance at a humble shopkeeper’s son, and yet she does. Indeed, Ruth is unexpectedly forward for the era, which certainly adds to her allure.

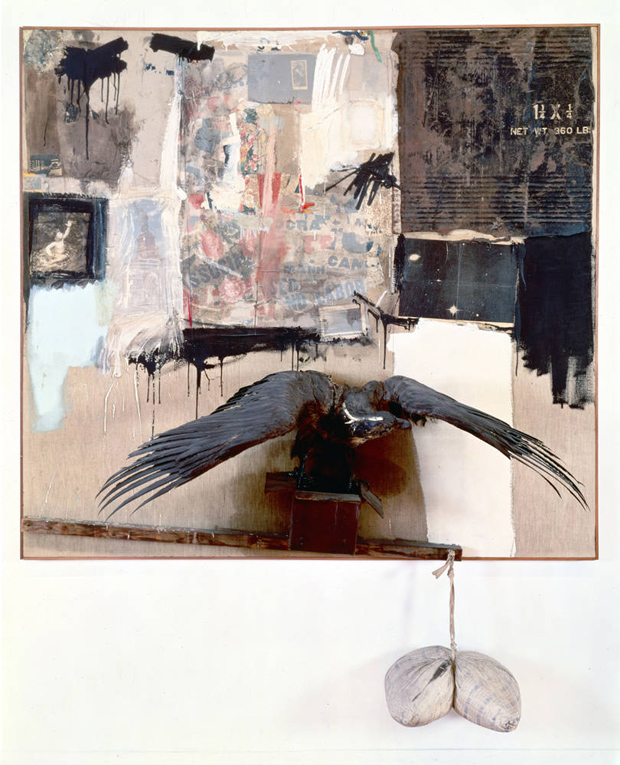

The parallels are deliberate: Ruth is enchanted by modern art, particularly works produced by the free-thinking students/residents at nearby Black Mountain College. Ira can’t begin to comprehend her fascination with the likes of Willem de Kooning and Robert Rauschenberg, but he’s willing to learn … just as Luke can’t imagine why anybody would pay thousands of dollars for “a bunch of black squiggly lines on a white canvas.” (Nor can I, for what it’s worth.)

Scripter Craig Bolotin wisely improves upon Sparks’ novel, by more elegantly integrating these two storylines. In the book, the hospital-bound Ira’s earlier life unfolds via “conversations” with his deceased wife; his actual interactions with Luke and Sophia are minimal. Bolotin’s decision to grant Sophia a larger part of Ira’s reminiscences, and to enhance their mutual bond, is far more satisfying.

Back in time, Ira and Ruth’s whirlwind courtship is interrupted by World War II (a segment seriously condensed from Sparks’ novel) and, in its aftermath, A Disastrous Battlefield Injury that has left Ira … less of a man. Can love endure?

Okay, my snarky tone isn’t entirely fair. Although it’s more fun to spend time with Luke and Sophia, there’s no denying the similarly endearing bond between Ira and Ruth, and our genuine consternation when things go awry. Much of the credit belongs to Chaplin — daughter of Geraldine Chaplin, and granddaughter of the legendary Charlie Chaplin — whose Ruth is a force of nature.

Huston’s young Ira spends much of the film transfixed by Ruth’s very presence, his mouth slightly agape: a mildly amusing and not terribly deep reaction, and yet one we understand completely. She is captivating, and her smile is to die for.

Meanwhile, back in the present, Sophia learns of Luke’s, ah, vulnerability: not from him, but from his worried mother (Lolita Davidovich, calm and understated, which is just right). Cue the usual stubborn response from the Man Who’s Gotta Do What A Man’s Gotta Do; cue the tears, hearts and flowers.

All of which sounds hopelessly maudlin, but … funny thing: By this point, we’re well and truly hooked by both storylines, and hopelessly invested in their outcomes.

Unless, of course, you haven’t a romantic bone in your body … which obviously was the case with the two insufferably rude women sitting nearby during Tuesday evening’s preview screening, who giggled derisively during the film’s entire second half. I get it: This is syrupy soap opera stuff, so if that ain’t your bag, don’t buy a ticket. Let the rest of us dreamy suckers enjoy it in peace.

At unexpected moments, and granted just the right camera angle by cinematographer David Tattersall, Eastwood looks and sounds spookily like his old man, during his younger days. It’s uncanny, at times, and this younger Eastwood takes full advantage of the heart-melting smile and luminescent gaze that seem his birthright. The bonus is that he’s a more expressive actor than Clint, if only by a slight margin … but I’ve no doubt Scott could become a star, given careful judgment of future roles.

The extraordinarily busy Robertson has parlayed considerable television work (most recently the adaptation of Stephen King’s Under the Dome) and big-screen supporting roles into some recent starring vehicles; between this and her high-profile turn in Tomorrowland, due in late May, she’s certain to make this year’s “promising young starlet” lists.

She’s just right here, giving Sophia an initially reserved, bookish wariness that melts persuasively as she throws herself, wholeheartedly and with the ill-advised impetuousness of young love, into this relationship with Luke.

The bull-riding footage is impressive, its authenticity overseen by the film’s association with Professional Bull Riders, with additional heft supplied by cameo appearances from a few PBR world champions. Tattersall and editor Jason Ballantine do impressive work with the riding sequences, which look realistically dangerous … particularly when it comes to a dread alpha-alpha bull dubbed Rango.

The film’s melodramatic virtues notwithstanding, it’s too damn long; 139 minutes is butt-numbingly excessive for this sort of romantic trifle. At the risk of succumbing to the obvious one-liner, this “ride” would have been more satisfying, had it been shorter.

Posted by Derrick Bang at 1:00 AM

– NOVEMBER 28, 2013POSTED IN: ARCHITECTURE, ART, FEATURE, HISTORY, UPDATES

Black Mountain College: Art Innovation and Education

By Max Eternity

“BMC was a crazy and magical place”

Lyle Bonge, Student 1947-48

How one responds to crisis often determines and confirms tragedy or triumph. Surely, John Rice knew of this when he led the charge to open an innovative new college in Asheville, North Carolina, some 80 years ago, calledBlack Mountain College.

“Black Mountain College was interested in educating human beings to become citizens of the world” says Alice Sebrell, “so that’s why things like grades, and in many cases degrees, were not as important as this deeper level of engaging the world—contributing to it, and being an active citizen.”

The college is now a museum, and Sebrell is its Executive Director.

Founded in 1933 by John A. Rice, the concept of the Black Mountain College drew from the philosophical principles of education reform as realized by American intellectual and psychologist, John Dewey.

As the school was being born, simultaneously Nazism was swelling in Europe and the United States was adrift in the Great Depression. Responding to the US crisis, and in his visionary commitment to uplift the economy and the morale of the American people, President Franklin Roosevelt created the Public Works Arts Project—a government program for artists that was later folded into and expanded on in the creation of the Works Projects Administration (WPA).

In the US, Roosevelt was championing the arts, while in Germany Adolph Hitler shuttered the Bauhaus in Berlin, Germany—a small art and design school founded by Walter Gropius that ultimately produced many of the world’s greatest creative, including Marcel Breuer, Joseph and Annie Albers, Wassily Kandinsky, Lily Reich and Mies Van Der Rohe. Among other things, shuttering the Bauhaus signaled the end of Germany’s Weimar Republic renaissance.

Along with Jews and those with alternative gender and sexual identities, Nazi Germany launched a brutal oppression against European artists and intellectuals who did not conform to the ideals of the state, and thus were deemed degenerate.

Of those who escaped, many of Europe’s best and brightest became students and teachers at choice schools in the United States, including Walter Gropius, who became department head of the architecture graduate program at Harvard University.

Joseph and Annie Albers, who both taught at the Bauhaus, were subsequently on the faculty at Black Mountain College.

In the 1940’s, Albert Einstein was on the Board of Directors at Black Mountain College.And while Jim Crow apartheid laws were being fully enforced throughout North Carolina and much of the nation, Black Mountain College included African-American artist, Jacob Lawrence—who is best known for “The [Great] Migration series,” which tells an epic visual story of the Black exodus from the South to the North—in its faculty.

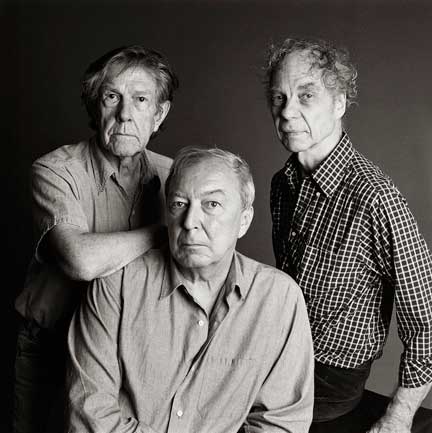

Though lesser known and smaller in size, many art historians consider Black Mountain College a parallel and peer to the Bauhaus, as it was equally as progressive and innovative as the Bauhaus. And during its 24 year lifespan, the school attracted and produced some of the greatest intellectual and creative talents of the 20th century. A partial listing of these figures include Josef and Anni Albers, Jacob Lawrence, Merce Cunningham, Buckminster Fuller, John Cage, Willem and Elaine de Kooning, Robert Rauschenberg, Cy Twombly, Kenneth Noland, Franz Kline, Arthur Penn, Ruth Asawa, M.C. Richards, Francine du Plessix Gray, Robert Motherwell, Charles Olson, Robert Creeley and many others.

Black Mountain College closed in 1957, yet decades later, and in this new century, the creative spirit and genius of Black Mountain College continues to inform of humanity’s greatest potential in art and education.

Black Mountain College (Asheville North, Carolina)

“I think that the direction that education has gone in recently where it’s all about testing and memorization is just diametrically opposed to what was going on at Black Mountain College“ says Sebrell, and in the following interview, Sebrell speaks further about the inspiration and lessons learned from Black Mountain College:

Max Eternity: What is the first thing that comes to mind when you think about Black Mountain College?

Alice Sebrell (AS): I think is probably a visual…because I’ve worked on so many projects that have to do with the visual aspect of the college—the artist and their work, or photographs of the college, or just walking the properties.

ME: And is there a common thread in this visual imagery?

AS: What comes up is the longing to have been able to experience it in person, rather than second hand. For me it’s more of a yearning for what appears to have been an incredibly intense, creative and charged experience for everyone who lived through, and those sorts of experiences don’t come along every day.

ME: And of the school’s founder, John Rice, I’ve read he was unflinching in his passion for education, that he was a genius, and his love for teaching and learning far outweighed his interest in institutional bureaucracy. To this point, Rice was no stranger to controversy. Who was this man?

AS: I think your description is accurate. He was a brilliant man.

I think he could be caustic or impatient with people sometimes; people who weren’t as quick or intellectual as he was. So I think he stepped on some toes, and you could say that about many figures at the college. They moved along at a quick pace. It was your job as a student or college to keep up. They weren’t going to coddle you.

ME: Others have their viewpoints, but from what you know about him what might John Rice say about himself?

AS: I’m guessing here, but I think he might say that he was misunderstood. And, I think he would say that even though the college didn’t last beyond 24 years, it was very successful, and that not all radical visions in education succeed in terms of time. That that’s not the true measure of success and that he started something great that’s had a lasting impact.

ME: It’s clear that the Bauhaus was influential to BMC, and in many ways the schools mirrored one another. Could you talk about some of the similarities and differences with each school?

AS: The first similarity that comes to mind is this idea of workshops in the arts, that that was the model that they had at the Bauhaus, and was brought here through Joseph and Annie Albers. Also, the idea of experimental performance, theatre and interdisciplinary activities in the arts—that would be a similarity. Another would be the fact that the Bauhaus moved—three different locations in its short life—and Black Mountain had 2 different homes. And that kind of thing would not allow for any sort of entrenched or ridged way of getting into a rut.

At the first place at Blue Mountain Ridge, they had to go away every summer. So each fall they set up a new, and that’s certainly uncommon.

ME: Yes, a radical approach to living and learning.

AS: They were living on the edge. At Black Mountain College they were always financially living on the edge. And at the Bauhaus, in the final years they too were living on the edge; in terms of the politics going on around them.

The main difference—from afar, my impression is that the Bauhaus was better funded, and larger.

ME: The Bauhaus was a government funded project. So, they had those coffers to draw from.